I am almost done with Jane Eyre. I have stopped at the chapter when Jane is teasing Mr. Rochester about St. John as she lets him believe she is in love with this Grecian statue.

I am almost done with Jane Eyre. I have stopped at the chapter when Jane is teasing Mr. Rochester about St. John as she lets him believe she is in love with this Grecian statue.

Now why might you ask did I select the basket of cherries and strawberries for this post? What possible connection do these have with Bronte’s novel? Strawberries only appear once when Adele is picking them in Chapter 23. Cherries as a fruit only appear in this chapter as well when Mr. Rochester is roaming his garden inspecting the fruit ripening on the trees. It is midsummer eve which is June 21 and the longest day of the year.

This is the chapter when Jane declares her love for Rochester and Rochester asks her to marry him. Most of that conversation takes place under the “great horse-chestnut” which is riven in two by a symbolic lightening bolt.

Both strawberries and cherries are fruits that only ripen in the early summer. And of course, in the nineteenth century, fruit only ripened in season — there were no strawberries in the winter, shipped from southern climes. The emphasis on Rochester walking his garden and inspecting each tree and bush turns him into an Adam figure and thus Jane into an Eve.

Here is how Bronte describes the scene;

While such honey-dew fell, such silence reigned, such gloaming gathered, I felt as if I could haunt such shade for ever; but in threading the flower and fruit parterres at the upper part of the enclosure, enticed there by the light the now rising moon cast on this more open quarter, my step is stayed—not by sound, not by sight, but once more by a warning fragrance.

Sweet-briar and southernwood, jasmine, pink, and rose have long been yielding their evening sacrifice of incense: this new scent is neither of shrub nor flower; it is—I know it well—it is Mr. Rochester’s cigar. I look round and I listen. I see trees laden with ripening fruit. I hear a nightingale warbling in a wood half a mile off; no moving form is visible, no coming step audible; but that perfume increases: I must flee. I make for the wicket leading to the shrubbery, and I see Mr. Rochester entering. I step aside into the ivy recess; he will not stay long: he will soon return whence he came, and if I sit still he will never see me.

But no—eventide is as pleasant to him as to me, and this antique garden as attractive; and he strolls on, now lifting the gooseberry-tree branches to look at the fruit, large as plums, with which they are laden; now taking a ripe cherry from the wall; now stooping towards a knot of flowers, either to inhale their fragrance or to admire the dew-beads on their petals. A great moth goes humming by me; it alights on a plant at Mr. Rochester’s foot: he sees it, and bends to examine it.

The scents of the flowers, the dew dripping down, the nightingale singing, the solitude and silence, the moths flying around — all are emblematic of the Garden of Eden. In Jane’s eye, Rochester almost seems like God as he stoops down to inspect the plants and the fruit. But he is much more so like Adam, waiting to claim his Eve. They sit and talk together under a this ancient tree, and, when the storm breaks, they rush into the house at just midnight. Then the tree is hit by lightning. And God passes judgement on their engagement in a terrific storm which blasts the tree (of Knowledge), dividing it into two parts connected only by the roots. When Bronte later describes the tree in the next chapter, the description cries out as foreshadowing and symbol.

In Bronte’s version of the fall, the temptor is not the woman but the man, who knowingly asks the woman to marry him, even when his mad wife lives on the third floor of Thornfield. It is rather refreshing for the sinner to be the man since the woman so often gets the blame.

And while Jane does pray to a patriarchal God when she is deciding to leave Rochester after the aborted marriage, the figure in the sky which seems to warn her and shelter her is feminine. In point of fact, throughout the entire novel, Jane is sheltered and protected primarily by women (Bessie, Miss Temple, Mrs. Fairfax, Diana and Mary) and only repressed by men (Brocklebhurst, St. John, Mr. Mason, Mr. Rochester [until he is purified]).

But back to cherries and strawberries. They are the sweet fruit of the summer and Jane herself never tastes them. Adele picks strawberries. Rochester inspects cherries. But Jane never eats. She is not like Lizzie in Christina Rossetti’s poem “The Goblin Market.” She drinks tea, eats porridge, has morsels of break and cake, once a sip of wine. But all her food is “cooked” in a Claude Levi-Strauss way. She does not eat from nature except when she runs away from Thornfield. Then in chapter 28, she eats bilberries and a crust of bread the night the coach leaves her at Whitcross. That is the only time.

Bilberries are closely related to blue berries. They grow in poor soils and are wild, not easily cultivated and thus not cultivated. Interestingly, they are supposed to improve night vision. Wikipedia says the pilots in the RAF ate them to improve their vision during World War II. They are also supposed to be good for heart conditions.

When Jane eats these berries, she is picking a fruit no one wants (really) and which only grows wild. Did Bronte know that bilberries were supposed to improve night vision? Would Bronte be suggesting that Jane is improving her “vision” by eating these berries? Now really that may be going too far.

I just did a search with the terms Victorian symbolism berry and stumbled on an article by Courtney Alexander entitled, “Berries as Symbols and in Folklore.” Here I learned that strawberries are associated with the Norse goddess of love Freya and in the Victorian era were symbolic of “sweetness in life and character” and had many positive associations. Well, no wonder Jane eats no strawberries!

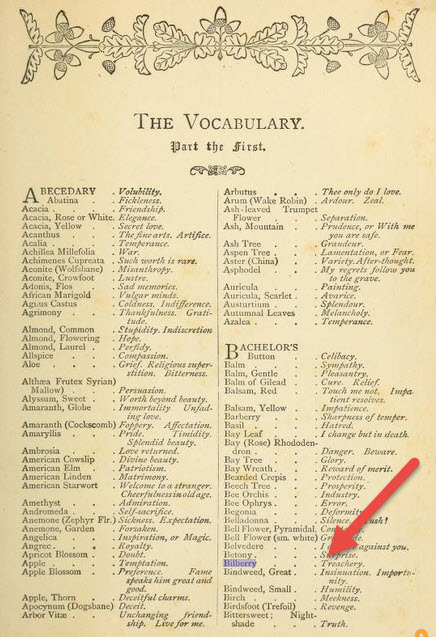

In 1869, John Ingram published a book called Flora Symbolica which listed flowers, fruits, trees, etc and their associated symbols. In this book, he lists that the bilberry represents “treachery.” Now that is interesting. Is Jane eating bilberries because she is treacherous? She will be soon assuming the alias Jane Elliot. Or is she eating bilberries to “eat” Rochester’s treachery and deceit and thus free herself of them? I rather like that idea. Instead of Jane becoming treachery and deceit by consuming bilberries (a la Claude Levi-Strauss), she is destroying those qualities by ingesting them. She will transform them by her own digestion.

In 1869, John Ingram published a book called Flora Symbolica which listed flowers, fruits, trees, etc and their associated symbols. In this book, he lists that the bilberry represents “treachery.” Now that is interesting. Is Jane eating bilberries because she is treacherous? She will be soon assuming the alias Jane Elliot. Or is she eating bilberries to “eat” Rochester’s treachery and deceit and thus free herself of them? I rather like that idea. Instead of Jane becoming treachery and deceit by consuming bilberries (a la Claude Levi-Strauss), she is destroying those qualities by ingesting them. She will transform them by her own digestion.

Would Bronte have known about the symbolism of bilberries? I think (cautiously), “yes.” Thus when she has Jane eat this fruit as opposed to any other, she is making a veiled statement about Jane’s moral development.