This is my third or fourth time teaching E.M. Forster’s enlightened novel A Room with a View, which chronicles how Lucy Honeychurch fights the armies of darkness (self-abnegation and sterility) to win her true love, George Emerson.

But first she has to get rid of Cecil Vyse (oh the humor of Forster’s infernally playful names for people and places).

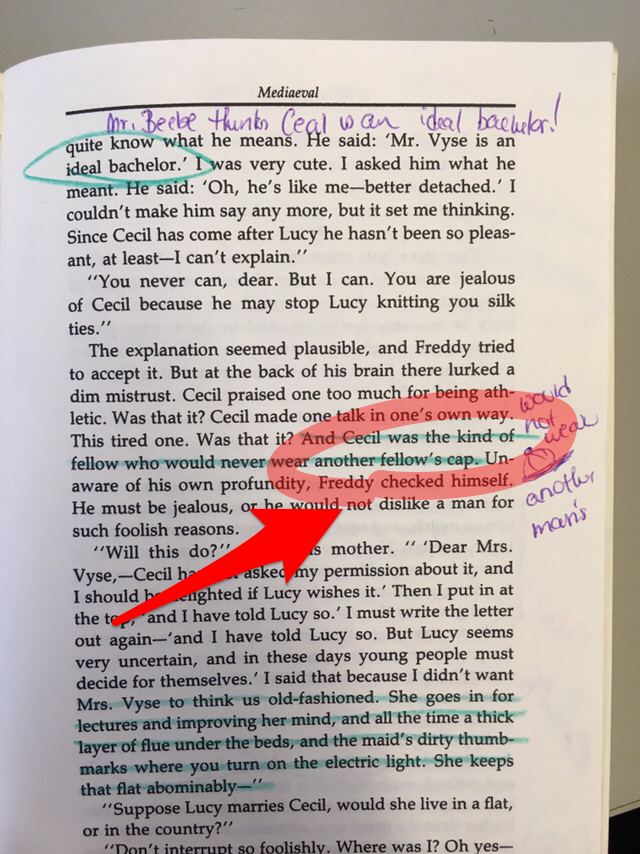

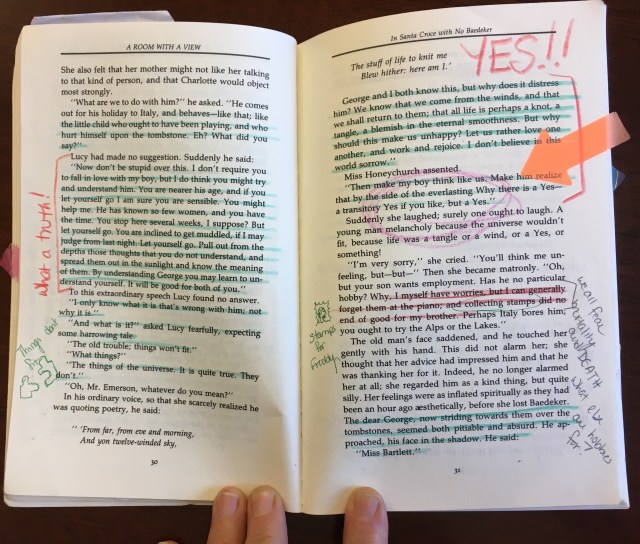

When Cecil first appears, Lucy’s brother tells his mother that he does not really like Cecil, because Cecil would never where someone else’s cap. See image below for textual evidence from Chapter 8:

Now this little aside of Freddy’s merely captures for me Cecil’s stuffiness. He would never ask to borrow another man’s cap. He would never want to wear someone else’s clothing. After all a cap might have dandruff or worse — creepy crawlies. And besides Cecil is more of a top hat sort of guy.

Freddy’s comment was another way for the narrator to express how Cecil deliberately sets himself apart from ordinary folks.

But it was not until this reading that I had my Eureka moment!

George Emerson is the sort who would wear another fellow’s cap. In fact, George Emerson wears someone else’s “bags.”

In the Twelfth Chapter (and so Forster names it), Freddy and Mr. Beebe call upon George and his father who have just moved into Cissie Villa. The father and son have not even finished unpacking, because Freddy and Mr. Beebe have to maneuver around a wardrobe which is standing in the middle of the passage. On impulse, Freddy asks George if he wants to have “a bathe.” This delights Mr. Beebe to no end.

Off the three men go to the “Sacred Pool.” They strip down and George looks “Michelangelesque” and they go swimming and dunking and galumphing in and out of the pool. That is until their exuberant playing is interrupted by the arrival of Lucy and Cecil and Mrs. Honeychurch. A mad scramble ensues to preserve Edwardian standards of modesty.

And here is where I finally make a connection (probably others — and here I include two long retired former colleagues who taught the book many times — have long before connected the dots.)

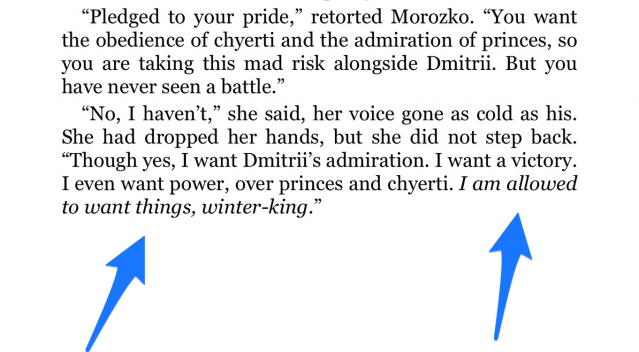

Forster has Freddy howl at George, “Emerson, you beast, you’ve got on my bags.” And here is the textual evidence to the left.

Look at the green circle around “bags” which is slang either for pants or men’s underwear. Given the age when Forster is writing, I think it more like to be a reference to pants, but nonetheless, there is a huge contrast symbolically between hat and pants/head and groin.

Cecil is all intellect with no sexuality. Look at what an abysmal failure his first kiss of Lucy is: he asks her permission, drops his nez pince between them, and considers the kiss himself unmanly. Forster calls Cecil an “ascetic” and uses adjectives like “celibate” to describe him.

George is an intoxicating (but subtle) amalgam of Eros and Philos. He kisses Lucy without her permission in a sea of foaming violets and he reads German philosophers — scaring Freddy whom the narrator says was “appalled a the mass of philosophy that was approaching him” (Twelfth Chapter). For George, Forster invents the word “Michelangelesque.” He uses the adjectives “radiant,” “personable.” He says George is “happy” and describes him as giving “the shout of the morning star.” What more do you want for a hero? Forster associates him with the sun, virility, the naked splendour of the Renaissance. Granted Forster does not call George a Modern David, but he might as well have done so.

What I find utterly amazing is that the minute detail of Cecil not wearing another fellow’s cap has niggled at my imagination for so many years. And only this year and only at this reading, did I finally connect the two references to clothing to create a new, deeper appreciation for Forster’s art and craft. Here’s to Freddy, Lucy’s delightfully irreverent younger brother, who was the character that helped me make the connection.

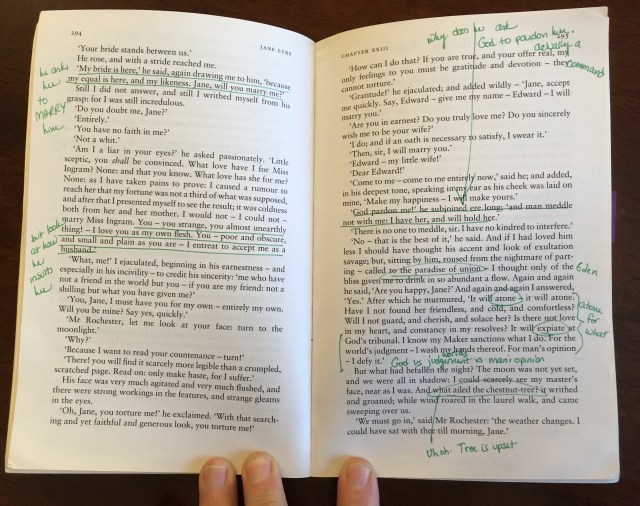

Recently I just finished the third book in Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy about a woman in medieval Russia who takes on the responsibility of trying to save her people of Rus from human depredations and supernatural threats and negotiate a compromise between Christianity and animism.

Recently I just finished the third book in Katherine Arden’s Winternight trilogy about a woman in medieval Russia who takes on the responsibility of trying to save her people of Rus from human depredations and supernatural threats and negotiate a compromise between Christianity and animism.

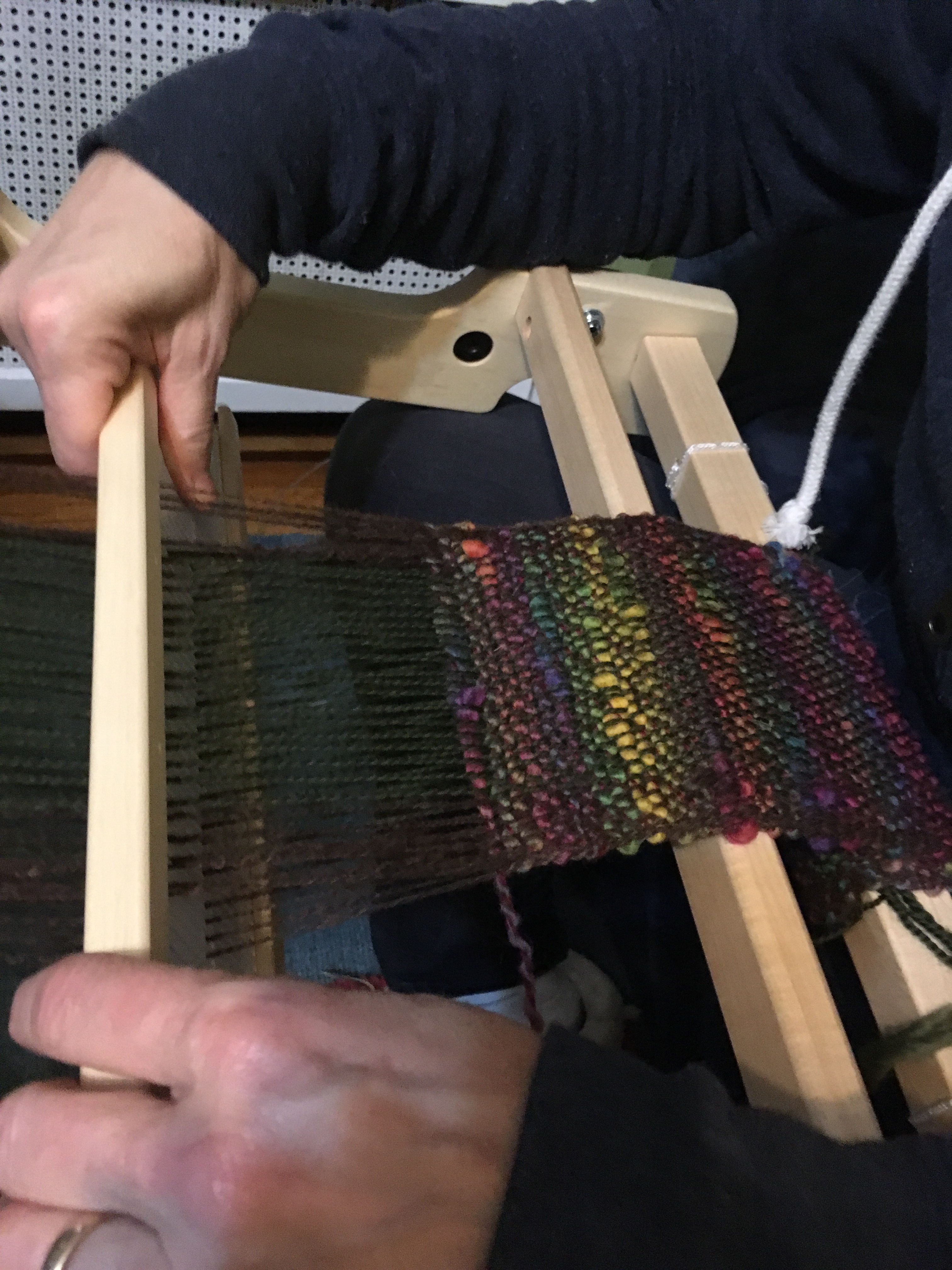

Weaving anything I am learning takes a great deal of yarn. For example, this third project used (conservatively) 940 yards of worsted weight alpaca and 200 yards of mohair. The warp was 112 inches long and there were 162 warp threads. This means the warp required approximately 500 yards. The weft required 16 inches for each pick and there were roughly 8-9 picks per inch. This means the weft required approximately 440 yards.

Weaving anything I am learning takes a great deal of yarn. For example, this third project used (conservatively) 940 yards of worsted weight alpaca and 200 yards of mohair. The warp was 112 inches long and there were 162 warp threads. This means the warp required approximately 500 yards. The weft required 16 inches for each pick and there were roughly 8-9 picks per inch. This means the weft required approximately 440 yards.

I used the full width of the loom — every slot and eye — and this actually is not a great idea because it makes winding the warp on the back beam tough because sometimes the side warp yarns fell off the paper which was supposed to separate each layer of the weft to keep the tension even.

I used the full width of the loom — every slot and eye — and this actually is not a great idea because it makes winding the warp on the back beam tough because sometimes the side warp yarns fell off the paper which was supposed to separate each layer of the weft to keep the tension even. The next day, I tied the knots at the ends of each fringe twist and used a tape measure to ensure the knots were roughly at the same spot. The last step was cutting off the excess yarn and again a tape measure was involved.

The next day, I tied the knots at the ends of each fringe twist and used a tape measure to ensure the knots were roughly at the same spot. The last step was cutting off the excess yarn and again a tape measure was involved. That comment got me thinking. What kind of loom would Penelope have used? I always imagined her sitting down to weave.

That comment got me thinking. What kind of loom would Penelope have used? I always imagined her sitting down to weave.